My early Christmas present

My dad handbuilt a new cabinet for my amp. I helped some.

The cabinet is mostly a replica of the Hot Rod Deluxe’s original housing, but it’s solid poplar, so it’s about 8 pounds lighter, and, well, the finish sure is spiffier than black or tweed. If you’re interested in knowing all the steps in building the amp, I made a build thread over on the gear page.

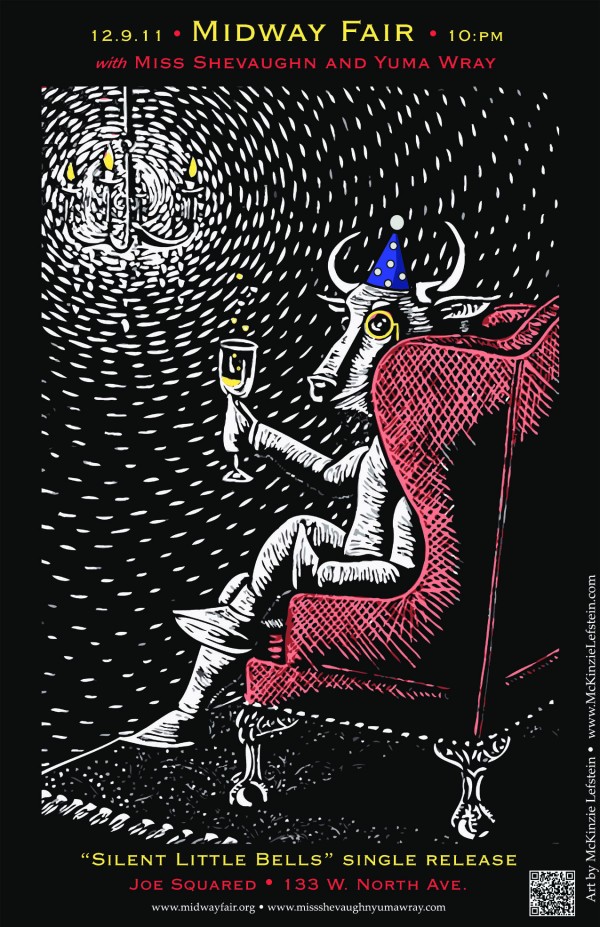

We're bringing our friends Miss Shevaughn and Yuma Wray to Baltimore for the first time. We played a bunch of shows with them over the summer. Oh, and here's your chance to get a copy of that poster McKinzie Lefstein made for us!

Back in the studio

So this is a bit of a surprise—I thought we’d be staying out of the studio this year, but we really got the bug to record Heather Aubrey Lloyd’s “Silent Little Bells,” so we’ll be heading out to Woodstock again to work with Chris Freeland in early November. We’ll also be rerecording an outtake from the sessions for The Distance of the Moon at Daybreak, “It Started Well,” which has only rarely been performed in public (and never as a full band). We’ve worked out a funky little drum beat and some unusual guitar sounds to go with Dylan-y lyrics, a jazzy progression, and a lot of local character.

“Silent Little Bells” will be the a-side, though. It’s an absolutely killer song by a local songwriter, and we haven’t played it in public as a full band yet, so the Joe Squared show will be everyone’s first opportunity to hear the full arrangement. I’m really excited about this song. It’s the song that actually got me into the idea of covering songs by local songwriters, and I’m not the only one around town who plays it, either, so I know it’s not just me. I’m really proud that we’ll be able to share it with our little corner of the world.

Okay, enough of the hype. Because there’s something else, besides recording our first cover, that’s a bit of a departure for us:

We’re not going to post this one publicly where everyone can listen to it. We’re not going to sell it. We’re going to give it away to people just for being on our mailing list. (There’s a link in the top right of our website to sign up, or you can click here, if you aren’t already on it.)

At some point that may have to change. There’s an upper limit to how many people can be on our mailing list before it starts costing us money we don’t make, and I have to pay Heather Lloyd for each copy of the song people download, so if for some reason we end up with one of those “first world problems” where too many people are downloading the song, I might have to put it up on iTunes or Amazon or something.

Oh, the EP will have a subtitle: Baltimerica 1. That should map out what’s going to be happening over the next year or so.

Joe Squared mini release show

So Dec. 9 will be our release show for the single/mini-EP, whatever you like to call it. We’re bringing our friends Miss Shevaughn and Yuma Wray to town. Spectacular vocals from Miss Shvaughn, and some big guitar sounds and a kickdrum provided by her partner Yuma Wray. We played a few shows with them over the summer, and it’s great to get them to our hometown. We’re talking with some friends about adding a third group, so we’ll let everyone know who that is once we know for sure.

Oh, right, a video

Anyway, this post also promised some video from our Cellar Stage show with the Kennedys. The show went great—we fit in pretty well with the headliners (who played a Fairport Convention song AND a Richard Thompson song), and we made a bunch of new friends. Hopefully we’ll be able to go back someday … maybe even with the full band. Paul Demmitt shot this video of our new song (pardon the incorrect song title):

Identity

I read something recently that got me thinking about artistic identity (this is paraphrased):

The old model was that a band would play live a lot, and go on tour before recording and releasing their album. Nowadays, instead of going on tour, bands record albums. … When they release a recording, it might get blown up in the bloggosphere (who’s always looking for the next big thing) before the bands has a chance to develop its artistic identity.

[If I could remember where I read it, I would like to the article.]

And this got me thinking about it even more:

I had the chance to watch the new Counting Crows DVD, August and Everything After Live at Town Hall. There’s an interview segment where Adam Duritz was talking about how he sat down and had to think about exactly what kind of band they were going to be. In the end he decided that he would force everyone to sit around in practice and really listen to each other. For those who aren’t familiar with the Counting Crows’ live performances, the band is famous for extensive changes to their songs live. That’s their identity.

I started wondering about what kind of band Midway Fair is.

A lot of this is particular to this band, but maybe someone else out there can take something from it, and maybe think about how it could relate to their own art.

It’s a tough question to answer. I’ve never really had to confront the question of defining my art in quite this way before.

I’ve certainly taken a stab at it. We’ve got handy little labels in the music biz, “genres.” Usually I tell people Midway Fair is a folk rock band. Well, sometimes that’s not true. Some people might decide that we’re just a rock band. Some might whip out the term “indie” (and I certainly use it to describe us, because even though I think it’s a lame descriptor, there isn’t another short word that means “challenging and idiosyncratic”). Some people call us “Americana,” probably my least favorite descriptor because it’s been coopted for a certain type of southern-derived alt-country, perverted from its original meaning of “representative of the folk art of America.” Technically, every musical form we play is represented in American folk idioms; but have you ever heard someone call a celtic band from Boston “Americana” — even though it would be perfectly correct to do so?

Brennan Kuhn from Petal Blight invented a term for us, “Baltimericana.” This is good because somehow it indicated that what we were playing represented Baltimore and wasn’t tied to being country-fied. I had started writing about my hometown more during the last record, and it felt right. There’s a lot of Celtic influence, and Baltimore has a wonderful Celtic music scene. Baltimore has a good indie rock scene. Folk artists galore and a surprising history of country. Several R&B and rap artists that have hit the big time. We’re pretty diverse.

But a genre isn’t an artistic statement. It can describe what a musician does — often better than most people will admit — but doesn’t get to the heart of matters. And it’s the heart that matters more. Right?

I don’t think we have a consistent artistic picture presented on our albums. Part this has to do with how we incorporated songs into the band before: I’d bring in a song with lyrics, chords, and a melody, and Tim and Jen would learn the song. This combined with my unwillingness or inability to focus on exactly what I like best meant that we would just all over the genre map, playing a little bit of everything. There was less of this on the second album, but the problem is still there.

However, lately, we started revisiting some songs we’ve played for a long time and making them sound more like “us.” We’ve played “Fisherman’s Blues” for a long time. Originally, we played it exactly like the Waterboys. It ought to have made perfect sense: It’s a folk rock song. We’ve borrowed the drum part (the end of “Edward Cain”). It’s how I would play the song on my own. And yet it didn’t feel right for Midway Fair. So we went back and reimagined it as if it were a our song, and we ended up with a different rhythm. Now it feel right. When a song clicks like that, it becomes more fun to play. The performance is better, and you’re more likely to communicate yourself to the audience. At least, that’s what I think.

I don’t know how to describe exactly what it means for something to be “a Midway Fair song” and not just “a song” yet, but it needs to have some of the tension that comes from all the people in the band. My songs with Jen, Tim, and Joe as backup musicians are not the same as a song where everyone is pulling in different directions and meeting in the middle. Jen and I in particular work very differently, and given that the bulk of writing and arranging (and, lately, performing) falls on us, most of the meeting in the middle comes from there.

Jen’s very precise, sophisticated, and clean. I’m not. I’m often a mess. Left to my own devices, I’ll get lazy about pitch and melody. But I can’t be like that if we’re going to do a lot of harmonies, which I’ve found is the thing that usually gets the best reaction.

It took a while to figure this stuff out. We’ve been a band for two years and only for the last couple months have we started acting like a multicellular organism. (And remember, we are an organism.)

That’s where it comes back to those indented parts up top. When you play a lot of live shows, it gives you more opportunities to take chances. Taking chances is how you learn what works and what doesn’t. Performance is a dialogue, where you and the audience learn from each other, in much the same way that being in a band means listening to each other and learning from each other. Creative expression is what comes out of synthesizing our unique experiences into something that others can’t have done before.

I don’t think live shows are the only way to find yourself as an artist, of course, but I do think that the best way to find yourself is by learning as much as possible from others, whether they’re your bandmates, your audience, a stranger talk to in a bar, a book, a song, anything external that communicates. Although there’s something to be said about your music pleasing yourself first and most, whatever you put out to other people should be representative of as much of yourself (whether you’re one person or a band) as possible. That way there’s no confusion about who you are, and the one person out there who likes that one thing you do will like the next song you do, and the next one.

It ought to have made perfect sense.

8/27/11 HOSTEL SHOW CANCELLED DUE TO HURRICANE

Of Olives and Sumac

This past Sunday, I finally got to make the private dinner that one of our Kickstarter campaign backers won. It took a few months to schedule it, but it seems pretty appropriate that it ended up being a couple weeks before the birthday dinner.

The Kickstarter donator was Diane, one of my “aunts” (I think she’s a second cousin once removed), which needless to say made it slightly awkward to have her “pay” money to have dinner with me and my wife. I’d have made her dinner if she’d asked. (I still have a bit of residual embarrassment over the Kickstarter campaign.)

I decided to go with a Mediterranean-inspired menu.

—

Beverages for the night were a bottle of Three Philosphers (not Mediterranean, but it’s good) and a Spanish Jumilla red wine.

First course:

Cheese plate with kefalotiri (a semi-hard sheep’s milk cheese reminiscent of Italian pecorino) and a barrel-aged feta with olives (Ceringnola, Mt. Athos, oil-cured black, and Greek jumbo brown). Served with homemade bread and olive oil. The kefalotiri was a big hit.

Second course:

A variation on the classic greek salad with baby spinach, oil-cured olives, feta, and red onion. Dressing was a lemon vinaigrette:

Juice of 1/2 lemon

1/2 cup salad oil

black pepper

1/2 tsp honey

I considered a pomegranate vinaigrette, but the main course had a pomegranate sauce, so I needed some variety.

Third course:

I thought for a bit about what would make a good main course for this meal. Gyros didn’t feel right, and lamb didn’t seem distinctive enough to stay in theme. There’s a few other dishes I like that I’ve just never made before, like fata, but the Pomegranate-sumac steak recipe I decided on is something I’ve made at home a couple times a year. (We don’t eat much beef, and we eat steak only once or twice a year.)

The original recipe I based this on used skirt steak, which was cheap at the time the recipe appeared in Cooks or Gourmet or whatever magazine I saw it in. Skirt steak is now $15 a pound or more, and that’s previously frozen, not even restaurant grade, and and it’s just not that good of a cut of meat to justify the cost. NY strip works just as well and has less waste.

The sumac used in this recipe is a Turkish spice. It’s not poisonous, obviously.

I used a low-sugar pomegranate juice because my aunt is diabetic. The original recipe adds sugar to the pomegranate juice, which I’ve found completely unnecessary. I find that this recipe serves 6 easily. A half pound of steak is a lot.

Pomegranate-sumac steak

2 lb strip steak

1 tbsp Sumac

1 tsp salt

1 tsp black pepper

Pat the steak dry. Mix the spices together and rub them on the steak. Let rest for a while, at least 10 minutes. You need to let it rest to let it come up to room temperature – it really has very little to do with the spices seeping into the meat or anything like that. I find it’s best to reserve a little of the sumac for after the steak has cooked.

Heat a pan to very high heat and sear the steak on all sides. (Medium rare is about 4 minutes on each side in my pans.) The best way is actually to do steak in the home is probably in a cast iron pan, get the pan extremely hot, and then plop the steak in the pan and stick it under the broiler. It cooks more evenly that way. But I don’t have a cast iron pan.

Transfer the steak to a cutting board or platter (something that the juices won’t go all over your counter) and let rest for about 10 minutes.

Sauce:

2 cups pomegranate juice, reduced to half

1 large shallot

3 tablespoons butter

1/4 cup tawny port

Juice of the other half of the lemon

Reduce the pomegranate juice and reserve. Dice the shallot and sauté in half of the butter until softened. Add the port and reduce to a glaze. Turn off the heat and add the pomegranate juice reduction, the drippings from the steak pan/cutting board, and lemon juice, and the remaining butter. Whisk until the butter is fully melted.

To plate, slice the steak and arrange five slices in the center of the plate. Spoon some of the shallots on top and pour some sauce around the plate. If you reserved some of the sumac, sprinkle a little on top.

I wish I’d taken some pictures. My aunt throws pottery and we used some of her homemade dishes, including some very cute green leaf salad bowls.

—

Before I go, I just want to get a complaint about foodies off my chest: I like pomegranates because they taste good, and my mom used to buy them when my sister and I were in grade school. They’re fun to eat. But now they’ve become uber-trendy, so pomegranate juice – which I paid less than $4 a bottle for in 2006 when I first learned this recipe – is now $8 or more.

And the reason isn’t just that it’s a trendy flavor. It also got picked up by the health food people, who can’t seem to enjoy anything without being convinced that it’s some sort of miracle food, and are currently in love with anti-oxidants. Like red wine: Let’s get bunch of scientists together and ask them if it’s good for us, because it tastes good and we can’t just Enjoy Things That Taste Good. It is good for us? Oh, okay, let’s drink it. Wait, it’s not? Let’s stop drinking it. This is a particularly American way of doing things, because if you like red wine and everyone’s telling you booze is evil, you have to have a witty retort like, “Well, I won’t be having heart attacks!” (Except from all the stress created by worrying about whether what you eat is the most healthy thing ever.)

So these anti-oxidants. The guy who first researched them was transferring knowledge of energy industry corrosion problems to human nutrition. And yet, how many of us have actually looked at the evidence – which suggests that they might in fact be harmful in large amounts (moderation in all things is still excellent advice!), not just unhelpful, and is at best inconclusive – instead of just buying into the idea that they were good because … all these packages started touting the amount of antioxidants in things like tea (which tastes good, and you should drink it for that reason). If you go back and look closely, you might even notice that these foods don’t even claim that antioxidants are good for you. They just brag about how much they have! Imagine if they started touting the amount of carbon atoms. We might all decide that carbon is particularly good for you.

-Jon

In our case, we played at Artscape, the biggest outdoor multiarts Festival at least in the mid-Atlantic region. We weren’t booked by Artscape and we don’t have street performance licenses. Suck it, usual channels!

A perusal of the submission guidelines for most festivals reveals that they either expect you to use some horrid 3rd party press kit service or to upload all your stuff – including videos, which are large files, you know – on their web site and then, after you’ve spent the better part of your afternoon doing so, they tell you three screens down the line that it’s going to cost you $35 to submit. Doesn’t mention if you’re going to get paid for the gig if you happen to get it, either, making it very difficult to determine what gamblers and stock traders and economists (but I repeat myself) call the “EV” or expected value.

My buddy Mosno did go through the Artscape website this year and get booked. And Acacia Sears did so by using a horrid 3rd party press kit last year. So Artscape has at least a modicrum of taste and therefore might have booked us if I had wanted to part with my $35.

But as you’ll see, this gig ended up being our most expensive ever. That’s why it’s not just dos, but don’ts, too. Read more…

CANCELLED Midway Fair’s Second Birthday Party: Dinner and a Show at the Baltimore Hostel

This is us, getting into shape to make dinner for you.

THIS SHOW IS CANCELLED DUE TO HURRICANE IRENE.

We’re proud to officially announce our Second Birthday Party, to be held at the Baltimore Hostel on August 27, 2011 (6:30-9:30; dinner served at 7:00). Last year our friends and fans joined us for a sold-out dinner in the beautiful ball room of this friendly hotel and ertswhile music venue in downtown Baltimore.

Click here to make your dinner reservation!

Reservations are required only for the dinner portion of the evening.

You can still come to the concert even if you don’t want to have dinner with us.

This year, we’re taking everything up a notch. The menu will be a little more sophisticated. We’ll have table service. [Edit: Sunspots was unable to make it for personal/personnel reasons, so the wonderful local duo Beggar’s Ride will be filling in!]

Dinner menu

Main courses

Coq au Vin (chicken braised in red wine with mushrooms, pearl onions, and lardons)

Sumac-pomegranite skirt steak (Limited availability)

Quinoa with grilled mushrooms and vegetables (vegan)

Sides

Home-grown salad with goat cheese, apple, and candied walnuts

Herbed new potatoes

Confit biyaldi ratatouille (roasted squash, peppers, and eggplant in tomato sauce)

Deserts

Chocolate mousse

Cookies and milk

Custard pie

Drinks

Tea, coffee, lemonade*

Click here to make your dinner reservation!

Presents: Collectable Posters with Specially Commissioned Art

This is the second in a series of four shows we’ll be doing throughout the year. All four seasonal shows will feature specially commissioned posters by local visual artists. This time around, our poster is by McKinzie Lefstein. McKinzie drew the art for the well-loved cover for Fireworks at the Carnival, and her use of bright colors, cuteness, and dark subject matter fits Midway Fair perfectly. McKinzie has gently altered her “Cheers! Year of the Ox” lineoum print and allowed a limited print run of these posters to be given away at the show.

Click here to make your dinner reservation for Midway Fair’s Second Birthday Party!

*No alcohol is allowed, per to the Hostel’s rules.

But that’s essentially arguing that critics changed enough tastemaker minds to create a schism between art and pop. Critics aren’t powerful enough (no matter what they think) to change more than a few minds, and artists are notoriously contrarian and iconoclastic. So something else must have happened.

But that’s essentially arguing that critics changed enough tastemaker minds to create a schism between art and pop. Critics aren’t powerful enough (no matter what they think) to change more than a few minds, and artists are notoriously contrarian and iconoclastic. So something else must have happened.